On Gone With the Wind Selznick and the Art of Mickey Mousing Summary

by Dr. Michael Pratt

one. Flick Music every bit an American Fine art Grade

Many people had a hand in the birth and early evolution of the motility motion picture in the tardily nineteenth century and early twentieth century in this state including Thomas Alva Edison who in 1887 invented the movie camera known as the Kinetograph in his New York studio with the help of his administration and the picture show projector known every bit the Kinetoscope. In 1888 George Eastman began to mass-produce celluloid curlicue moving-picture show for still photography at his plant in Rochester, New York. In 1896 Edison brought the Vitascope to the market based on the Cinematopgaphe of the Lumière brothers and Auguste and Louis.[1] In 1903 ane of the starting time milestones in the history of the move motion-picture show was produced by Edison'south "Black Maria" movie studio in West Orange, New Jersey with the production of what is considered the outset narrative film and the get-go film of the so-chosen "western" genre – The Cracking Train Robbery (based on an actual incident by Butch Cassidy and his Hole-in-the-Wall gang).[two] By 1908 at that place were xx movie producing companies in America and between eight,000 and x,000 film theaters (and so-called Nickelodeons). "Feature films made motility pictures respectable for the middle class by providing a format that was analogous to that of the legitimate theatre and was suitable for the adaptation of center-form novels and plays. This new audience had more than enervating standards than the older working-form one, and producers readily increased their budgets to provide high technical quality and elaborate productions." [3] The result was the emergence of the "movie palace", one of the first of which was the 3,300 seat Strand in the Broadway district of Manhattan in 1914. By 1916 there were more than 21,000 such movies theaters in America, marker an end to the Nickelodeon era and the kickoff of the Hollywood studio organisation of producing movies (dominating the industry through the 1950s). Literally thousands of films were produced during the silent film era betwixt 1904 and 1927 giving rise to stars such as Charlie Chaplin, Fattie Arbuckle, Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Buster Keaton, Laurel and Hardy, and Lon Chaney. Past the early 1920s in that location were forty one thousand thousand Americans attention movies each calendar week. (ibid.)

Everything changed forever in 1927 with the release past Warner Bros. of The Jazz Vocalist starring Al Jolson. For the start time the audience heard a voice and would never once again be content with silent movies. Such was the demand for "talkies" that "The wholesale conversion to sound…took identify in less than 15 months between late 1927 and 1929, and the profits of the major companies increased during that menstruation past as much as 600 percent." [4] Initially film scores were limited to Chief Titles and Credits with all else being diegetic (sounds whose sources are visible on the screen or whose sources are implied to be present past the action of the film).[5] It presently became apparent that a musical score was non only essential to a moving picture merely highly benign as well and soon non-diegetic scores began to appear (sounds whose sources are neither visible on the screen nor take been implied to be present in the activity – ibid.). Dramatic scores appeared. Scores whose presence in sound made the film better (a premise in Hollywood amidst movie composers is that a proficient score can make a bad film amend and a practiced film cannot be hurt by a bad score). "In the hands of clever composers, a true musical drama is created. Erich Korngold persuaded you that Errol Flynn was actually Robin Hood, Max Steiner told you what it was like for a Southern aristocrat to lose the war and a way of life, Miklos Rozza let you know how Ray Milland felt on a lost weekend, and Bernard Hermann terrified you as some weirdo butchered Janet Leigh in the shower. If you believed Dana Andrews really loved Laura, thank David Raskin; or if you lot shared Dana'southward mind wanderings as he sabbatum in the nose of a wrecked B-36, tip your hat to Hugo Friedhofer. If your heart went out to Gary Cooper as he waited for those gunmen at high noon, you might give a thought to Dimitri Tiomkin; and if you lot really thought Jennifer Jones saw the Virgin Mary, and so light a little candle to the memory of the late Alfred Newman. And Joan Fontaine was absolutely right when she felt Manderley was haunted, but it wasn't spirit of Rebecca – it was Franz Waxman's music." [half-dozen]

2. Max Steiner's Biography

Maximillian Raoul Walter Steiner was built-in in Vienna on May ten, 1888 and died in Beverly Hills on December 28, 1971. His father and grandpa were theatrical producers who produced the operettas of Franz von Suppe, Jacques Offenbach and Johann Strauss. Max was a child prodigy studying piano with Johannes Brahms, orchestration with Richard Strauss and conducting with Gustav Mahler. After completing a four year course of musical study at the Vienna Conservatory in one year, Max worked throughout Europe from 1904 to 1914. Finding himself in London at the outbreak of Globe War I he was classified every bit an undesirable alien and chop-chop emigrated to New York where he worked on Broadway for the next fifteen years as a copyist and afterward equally an arranger, orchestrator and usher of musicals and revue shows, on and off Broadway. "These shows included the Gershwins' Lady Be Good! (1924), Kern's Sitting Pretty (1924) and Youman's Rainbow (1928). His just Broadway show, Peaches, was composed during this period. He also worked extensively with Victor Herbert, arranging many of the composer's trip the light fantastic numbers, and acting as the musical director for a touring product of Oui Madame (1920). Herbert'south influence can be seen in the attention to orchestration which characterizes Steiner's motion-picture show scores. For musical theatre he learned to combine small numbers of instruments to create the impression of a fuller orchestral sound, a skill which was to evidence useful in the nether-funded music departments of Hollywood." [7]

In 1927 Steiner orchestrated a Broadway show called Rio Rita which was later purchased by RKO Pictures for the pic. As a consequence of Steiner's ability to create large sounding orchestrations with a small orchestra, he was hired by RKO to do the flick version. The first original film score by Steiner was in 1930 for the film Cimarron. Steiner'due south career as a flick composer actually took off when the thirty twelvemonth-onetime David O. Selznick came to RKO in 1932. With the film Symphony of Six 1000000: "David said, "Do y'all call up you could put some music behind this thing?" Music until then had not been used very much for underscoring – the producers were agape the audience would ask "Where'south the music coming from?" unless they saw an orchestra or a radio or phonograph. Simply with this flick nosotros proved scoring would work." [eight]

Steiner presently became known for his ability to depict things musically: Leslie Howard's limp in Of Homo Bondage, a domestic dog walking along a corridor in Since You Went Away, or the water dripping in Victor McLaglen'due south cell in The Informer. This technique, known as "mickey-mousing" proved to be quite effective for Steiner. The film that brought Steiner to anybody'south attention was Rex Kong in 1933. "In addition to composing scores, Steiner also acted as the arranger-conductor on many RKO musicals. He was the musical managing director on well-nigh of the Fred Astaire-Ginger Rogers pictures." (ibid.) In 1936 Steiner left RKO for Warner Brothers. "It's doubtful if any composer in history worked harder than Max Steiner. In his first dozen years for Warner Bros. he averaged eight scores a twelvemonth, and they were symphonic scores calling for forty and 50 minutes each. His acme twelvemonth was 1939 when he worked on twelve films including Gone With the Air current, the longest score and so written. Steiner'southward career with Warner Bros. spanned almost thirty years and included scores for almost 150 films." (ibid.) A partial list of Steiner flick scores would include Rex Kong, 1933; Little Women, 1933; Of Human being Bondage, 1934; The Informer, 1935; The 3 Musketeers, 1935; The Charge of the Low-cal Brigade, 1936; A Star is Born, 1937; The Life of Emile Zola, 1937; Jezebel, 1938; Gone with the Current of air, 1939; They Died with their Boots On, 1941; At present, Voyager, 1942; Casablanca, 1943; Arsenic and Old Lace, 1944; Since You Went Away, 1944; Mildred Pierce, 1945; The Big Sleep, 1946; Life with Father, 1947; Johnny Belinda, 1948; Key Largo, 1948; The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, 1948; The Glass Menagerie, 1950; This is Cinerama, 1953; The Caine Mutiny, 1954; The Searchers, 1956; A Summertime Identify, 1959; The FBI Story, 1959; and Spencer's Mountain, 1963. He received numerous Oscar nominations, winning the award three times for the films Now Voyager, The Informer and Since you Went Away. The terminal film scored by Max Steiner was Those Calloways in 1965. Steiner died in 1971 of cancer.

3. The Score to King Kong (1933)

RKO was in fiscal difficulties and nearing bankruptcy. It had already spent nearly a half one thousand thousand dollars producing a film nigh a fifty foot tall gorilla named Male monarch Kong. Steiner was in accuse of the music department at the studio in a time when a single motion-picture show had a budget for a maximum of a three hour recording session with a ten piece orchestra. For King Kong information technology was decreed even this would not exist allowed and that Steiner had to use music tracks from other recent film scores such as Picayune Women (!) The film'due south manager Merian C. Cooper was convinced of the potential for the moving-picture show and the importance of a skillful score by Max Steiner. "Cooper said the magic words, which I quote: 'Maxie, go ahead and score the moving-picture show … and don't worry about the cost, because I will pay for the orchestra.' And and then he did, to the tune of fifty thousand dollars – an enormous sum to expend on music so; and to hear him tell it, it was worth every dime. The music meant everything to that motion picture, and the picture meant everything to RKO, because it saved the studio from defalcation…. The impact of King Kong on the movie going public was astonishing. It emerged into a land frightened, impoverished, in the grip of the Swell Depression. However, on the very day when President Franklin D. Roosevelt closed the banks and alleged a moratorium – a menses of grace on the repayment of debts – the post-obit advertisement appeared in a New York Urban center paper: 'No money! Nevertheless New York dug up $89,931 in iv days to run across King Kong at Radio Urban center, setting a new all-fourth dimension globe's record for attendance at any indoor attraction.'" [9] In a time when the boilerplate ticket price to a film was 10 cents, the price of admission charged for Rex Kong by Grauman's Chinese Theater in Hollywood was 50 cents to seventy-v cents for matinees and fifty cents to a dollar for evening screenings. Opening night was an incredible $3.30. The fifty foot gorilla may have been the initial draw but the Max Steiner score certainly contributed to the on-going success of the film over the years. "[Merion C.] Cooper was a potent supporter of [Steiner's] work on his own The Most Dangerous Game, released several months before Kong, and he continued over the years to secure the services of Steiner whenever possible – sometimes undercover because of contractual conflicts (This is Cinerama, etc.). 'So far equally my experience goes he was the originator, the creator, the dramatist of music on the screen', said Cooper." [ten]

"Steiner used what would exist considered for the time a large orchestra for motion-picture show scoring – 46 players)." (ibid.) Being a classically and European trained musician of the late nineteenth and early on twentieth centuries, Steiner fell nether the influence of composer Richard Wagner (as did almost the whole of the musical world at the time). Equally a result he used Wagner'southward leitmotiv method of composing for his film score. Steiner is often quoted every bit saying "If Wagner had lived in this century he would have been the number i film composer".

Max Steiner Conducting the King Kong Studio Orchestra [11]

Utilizing Wagner'due south leitmotiv system of assigning a theme for all of the principal characters and events and using them developmentally in a symphonic fashion allowed Steiner to craft a film score which was both musically dramatic and story enhancing (to the aforementioned consequence every bit Wagner's usage in his Band Wheel of operas). The "Main Championship" music opens with Male monarch Kong'south three annotation motive; heard throughout the entire score in many sections and guises, but always identifying King Kong himself. Rex Kong's leitmotiv is usually descending merely sometimes rising (or a combination where the three notes descend but are repeated in a rising sequence, for example, as Rex Kong approaches).

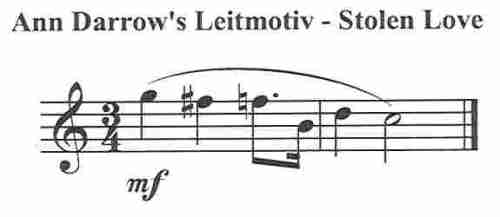

Scored in full contumely and low strings these ominous three notes give the audience the expectation of what is to come up in both scope and terror. Followed by a brief fanfare the "Main Title" music continues with the "Stolen Love" theme of the movie's heroine, Ann Darrow. Eventually this theme refers not only to her love for First Mate Jack Driscoll, who saves her life, but also to her relationship to Kong himself, which is the core of the moving picture (which ends with the famous line "Information technology was dazzler killed the beast").

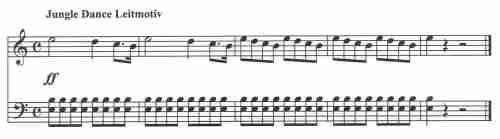

The "Principal Title" music continues with its tertiary motive, the jungle trip the light fantastic seen on Skull Island when the main characters first state.

Later on the jungle dance and a second fanfare, the Kong leitmotiv returns scored in a much more than soft, lush, and romantic fashion. The listener is signaled that non everything with Kong will be terrifying. Steiner's constantly evolving apply of these motives not simply dramatically underscores the action of the motion-picture show but makes the movie maker's near impossible chore of turning a fifty foot tall gorilla into a sympathetic figure a realistic goal, achievable in big part by audition sympathy aroused past the musical score.

Kong's motive, utilized throughout the unabridged score, is heard in sections such equally "The Entrance of Kong", "Log Sequence", "The Cave", "The Theater Sequence" (in New York), "Kong Escapes", "Elevated Train Sequence", "Aeroplanes", and, or course, the "Finale". The Stolen Beloved motive of Ann Darrow is heard in "The Sea at Dark – Forgotten Island" with Jack Driscoll, and afterwards in "The Cavern" with Kong (it is largely through Steiner's score that the fondness of the gorilla for a adult female is portrayed). Christopher Palmer notes the iii note Kong motive "profoundly facilitates its contrapuntal inclusion in many different contexts. At one point it becomes the motif of Kong'southward approach. Later on it is transformed into the beginning phrase of the march played in the theater when Kong is put on public display in New York (doubtless a nostalgic backward look on Steiner'southward part at his years in the pit on Broadway). A particular subtlety is the way in which at certain critical moments – notable in the finale, in which Kong falls to his death from the Empire Country Building afterward depositing Fay Wray in a place of safety – the Kong theme and the Fay Wray theme [Secret Love] (which in its pristine state is a pretty waltz melody) really converge and become one thus musically underlining the tale of Beauty and the Brute." [12] The Jungle Dance motive begins with the "Aboriginal Sacrificial Dance" and is heard later in the "Return of Kong". In the "Aboriginal Sacrificial Dance", when the leader of the tribe start sees the Americans he stops the dance and approaches them as they go on to motion-picture show what appears to exist some sort of ceremony. As he approaches them he walks with heavy and deliberate footsteps. Steiner's score uses a descending scale in perfect synchronization with these footsteps. This deliberate utilise of music to non only underscore merely mimic the activeness on the screen is Steiner'due south first use of what would later be know as "mickey-mousing".

"Steiner composed this music in the full Wagnerian orchestral tradition…com[ing] up with compromises such as woodwind players beingness asked to play upward to four different instruments within a given cue, or a viola actor to run quickly (but quietly) over to the celesta and play a few notes, or even having some of the violin players change over to violas for some passages. Excerpts from Steiner's score turned upwards in several subsequent scores, such as The Son of Kong, The Last Days of Pompeii, The Terminal of the Mohicans, and Back to Bataan." (ibid., The Consummate 1933 Film Score)

Noted moving picture composer Danny Elfman says "I think it is important to remember that when Steiner set up downwardly to score King Kong there were almost no references. He was practically starting from a make clean slate – uncharted territory. So many things that Steiner did we have for granted now that the linguistic communication has been divers. Steiner really is the grandfather of this wonderful art grade." (ibid.)

4. The Score to Gone With the Current of air (1939)

In 1936 one of the most pop and best selling books of all time was published, Gone With the Wind by Margaret Mitchell. David O. Selznick immediately acquired the rights to motion picture the book and actual filming began later many delays in December 1938. In a memo in 1935 Selznick stated that "'he considered the right score a major element in the success of a pic…and there is no one in the entire field within miles of Max' [Steiner]. Two months later Steiner was signed every bit musical director of Selznick International." [xiii] Two years later on Selznick refers to the music for GWTW for the first time proverb "My first choice for the job is Max Steiner and I am sure Max would give annihilation in the world to practise it" (ibid.) The borderline for the premier was set for Atlanta, Georgia on Dec fifteen, 1939. Steiner was busy completing the scores for We Are not Lonely, Iv Wives, and Intermezzo (three of the twelve movies Steiner scored in 1939 (!) including the longest score which had ever been written for a movie for GWTW). Steiner complained to Selznick that it was impossible for him to meet this borderline but Selznick discounted this "largely because Steiner is notorious for such statements and works well under pressure, and I am inclined to take that chance and bulldoze him through." (ibid.) Well-nigh the process of writing, orchestrating and recording the music to GWTW, Hugo Friedhofer recalls "The whole thing had a really nightmare quality about information technology, because we were really under pressure. Nosotros never started recording until after dinner and so until two, sometimes three in the morning time…then we would go dwelling, grab a couple of hour'south slumber, write with orchestrators and copyists breathing down our necks, grab a bite before recording, and and so beginning the whole thing over once again. And this went on for I don't know how many weeks." (ibid.) According to Tony Thomas "Steiner says he managed to alive through these weeks merely with medical assist; a doctor came frequently to his home and gave him Benzedrine so that he could maintain a daily piece of work routine of twenty hours at a stretch." (ibid., Themes from The Vienna Woods)

As was his practice, Steiner used Wagner's leitmotiv method of assigning a theme for all of the primary characters and events. In addition Steiner used patriotic tunes from the era (Civil War) and other Southern and pop songs (many equanimous by Stephen Foster). All eleven principal characters have their own motive. More important than all of them, though, is the theme for Tara, the O'Hara family unit plantation. Not simply is this motive the theme which identifies the moving-picture show, it has become an iconic musical symbol for the grandeur of the Southern, aristocratic way of life itself. Steiner masterfully uses the upwards leaping octave to musically capture both the grandeur of Tara (and the Due south) and the huge scope of the topic (and of the motion moving-picture show itself).

In King Kong Steiner used orchestrations which were heavy with woodwinds, brass, and percussion and short, "punchy" themes for dramatic effect. In the score to GWTW he utilizes more string orchestrations, writing with a much more sweeping scope to the melodies. Some of the writing, for instance "In the Library" where Scarlet first meets Rhett Butler, contains many sections for solo violin.

The 1939 Academy Awards nominations for best original score included twelve films including Of Mice and Men (Aaron Copland), Wuthering Heights (Alfred Newman), and Nighttime Victory and Gone With the Wind (both Max Steiner) with the award going to Herbert Stothart for The Wizard of Oz (about the only category in which it beat GWTW). In 1942 Margaret Mitchell wrote to David O. Selznick "At the Thou Theater here in Atlanta, they play the theme music from Gone With the Wind in the interludes of the pictures and when the terminal operation of the nighttime is over. Frequently I remain in my seat to mind to it because it is so beautiful." (ibid.)

An interesting footnote is that the huge fire created to simulate the burning of Atlanta in Gone With the Air current was achieved primarily by burning the gigantic wall from Male monarch Kong.

5. Max Steiner'due south position every bit a landmark composer of American film music

Ray Harryhausen (the creator of the magical furnishings seen in such films Disharmonism of the Titans, Jason and the Argonauts, and, of course, Male monarch Kong) had the following to say about Max Steiner: "Steiner's output varied to such extremes of filmed discipline matter that it actually boggles the listen…He was one of the few "Hollywood Greats" who could instantly inject "the spirit" of the screen story into the audio accompaniment thus enhancing the visual epitome many times over with emotional values only the ear can perceive…Steiner tackled these subjects with originality, dramatic charisma, and ataraxy, indelibly enhancing our visual images to unforgettable proportions. His many imitators before long fell into oblivion." (ibid., King Kong, Marco Polo)

Ray Bradbury (author of The Martian Chronicles) says "At one of the Academy Awards broadcasts, an eminent composer said: 'Cheers to the Academy, the members of the Academy, and to Tschaikovsky, Berlioz, Vivaldi, Moussorgsky, and Bach.' My response to cinema music history would become like this: 'Thanks to Max Steiner'" (ibid.)

Copyright 2010 by Pratt Music Co.

FOOTNOTES

[ane] Encyclopedia Britannica, 2006, "Motion Flick, History of the," http://www.search.eb.com/eb/article-52136/ (accessed January 22, 2006).

[two] Tim Dirks, "The Great Train Robbery (1903)," The Greatest Films, 1996, http://world wide web.filmsite.org/grea.html. (accessed January 22, 2006).

[3] Encyclopedia Britannica, 2006, "Pre-earth War I American Picture palace," http://www.search.eb.com/eb/article-52140/ (accessed Jan 22, 2006).

[four] Encyclopedia Britannica, 2006, "Conversion to Sound," http://www.search.eb.com/eb/article-52149/ (accessed January 27, 2006).

[five] Bordwell-Thompsson & Reize-Millar, "Diegetic And Non-diegetic Sounds," The Art Of Filmsound.org, 2006, http://www.filmsound.org/terminology/diegetic.htm#nondiegetic/ (accessed January 27, 2006).

[6] Tony Thomas, "What's the Score?" [Page 5] in Music for the Movies, (Los Angeles: Silman-James Printing, 1997).

[vii] Kate Daubney (with Janet B. Bradford), "Steiner, Max," Grove Music Online, 2006, http://www.grovemusic.com/ (accessed Jan 28, 2006).

[8] Tony Thomas, "Themes from the Vienna Woods," [Folio 146] in Music for the Movies, (Los Angeles: Silman-James Press, 1997).

[9] David Raskin, "Max Steiner," American Composers Orchestra, 1995, http://www.americancomposers.org/raksin_steiner.htm. (accessed January 28, 2006).

[ten] Max Steiner, "King Kong," Original Motion Moving picture Sound Track, Turner Archetype Movies R275597, 1933, CD.

[eleven] Max Steiner, "The Complete 1933 Film Score," King Kong, Marco Polo B-223763, 1997, CD.

[12] Christopher Palmer, The Composer in Hollywood [Pages 28-ix] (Great Great britain: Marion Boyars, 1990).

[thirteen] Max Steiner, "Original Move Picture Soundtrack," Gone With the Current of air, Turner Classic Movies R272822, 1939, CD.

Source: https://michaelpratt.wordpress.com/2009/09/03/the-film-music-of-max-steiner-with-emphasis-on-king-kong-1933-and-gone-with-the-wind-1939/

0 Response to "On Gone With the Wind Selznick and the Art of Mickey Mousing Summary"

إرسال تعليق